$1 billion example of the Thermocline of Truth

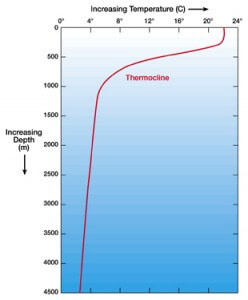

In a post here last week, I made reference to what I call “the thermocline of truth.” The basic idea is simple: those in the trenches of a large project know how badly it’s going, while those at the top think everything’s fine; the level at which the ‘truth’ stops is somewhere in the middle. As the project deadline appears, the bad news makes its way ever close to the top, until the project — usually shortly before the project delivery date — suddenly is delayed or canceled.

Well, doing some research online this weekend, I ran across an IEEE Spectrum article from last November about a $1 billion system re-engineering failure at the US Air Force, an attempt to “replace 240 outdated Air Force computer systems with a single integrated system so that the Air Force could finally come up with an auditable set of financial records.” What struck me was this description of how this project managed to drag on for seven years and consume $1 billion without producing anything:

In the report, IDA [the Institute for Defense Analyses] states that on these projects, “Program managers are unable to deliver a completely factual version of their status to leadership if it contains any element that could be considered significantly negative. To do so is perceived as weakness in execution even though the root causes may be out of the control of the program manager. Program managers fear that an honest delivery of program status will result in cancellation. As a result of this, leadership is unable to be effective in removing obstacles to program success.”

In short, no one in the DoD leadership chain wants to hear bad news. The IDA report further noted that bringing up bad news required “courage,” which apparently is in short supply in DoD ERP projects in particular and, from my experience, DoD programs in general.

I couldn’t have said it better myself. In fact, what I actually said was:

Third, managers (including IT managers) like to look good and usually don’t like to give bad news, because their continued promotion depends upon things going well under their management. So even when they have problems to report, they tend to understate the problem, figuring they can somehow shuffle the work among their direct reports so as to get things back on track.

Fourth, upper management tends to reward good news and punish bad news, regardless of the actual truth content. Honesty in reporting problems or lack of progress is seldom rewarded; usually it is discouraged, subtly or at times quite bluntly. Often, said managers believe that true executive behavior comprises brow-beating and threatening lower managers in order to “motivate” them to solve whatever problems they might have. . . .

Successful large-scale IT projects require active efforts to pierce the thermocline, to break it up, and to keep it from reforming. That, in turn, requires the honesty and courage at the lower levels of the project not just to tell the truth as to where things really stand, but to get up on the table and wave your arms until someone pays attention. It also requires the upper reaches of management to reward honesty, particularly when it involves bad news. That may sound obvious, but trust me — in many, many organizations that have IT departments, honesty is neither desired nor rewarded.

This is a very pervasive pattern in large-scale IT failures. In the meantime, if you want to read the full IDE report (PDF), you can find it here.

![The Meltdown/Spectre CPU bugs: a dramatic global case of the “Unintended Consequences” pattern [UPDATED 4/4/18] The Meltdown/Spectre CPU bugs: a dramatic global case of the “Unintended Consequences” pattern [UPDATED 4/4/18]](http://bfwa.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/intel-cpu-150x150.jpg)

Comments (4)

Trackback URL | Comments RSS Feed

Sites That Link to this Post